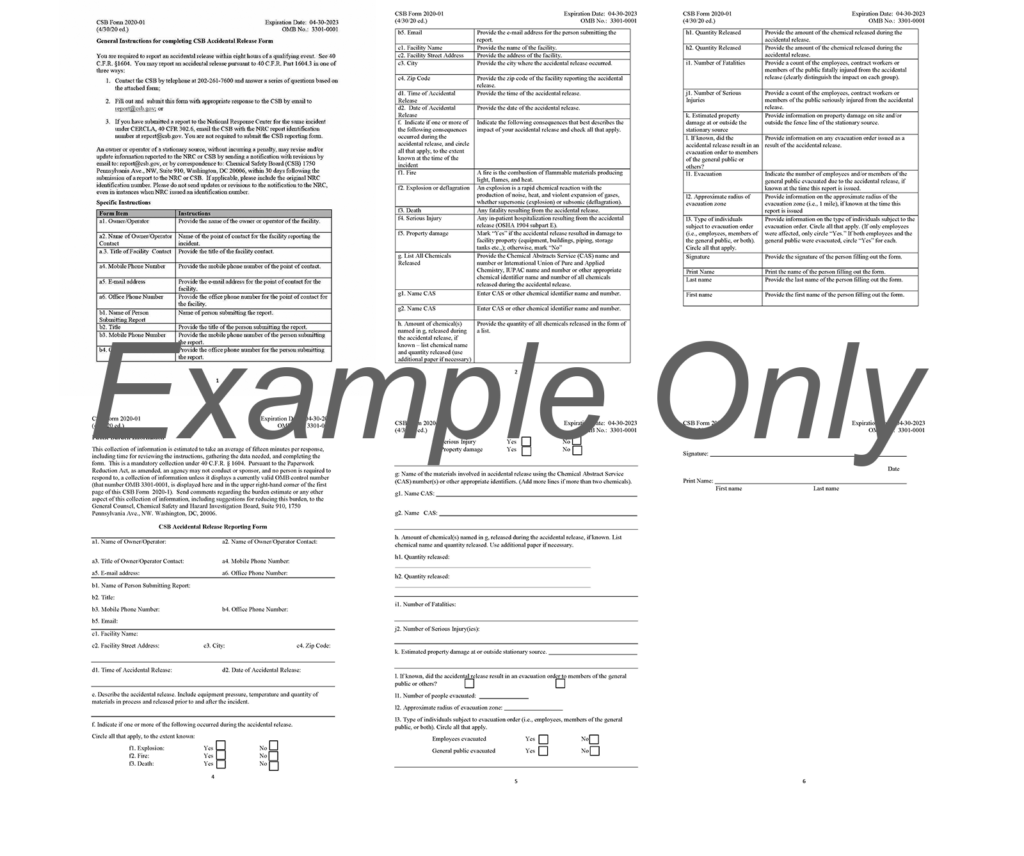

The terms “timely” and “as soon as possible” are used in the PSM and RMP standards, the mid-nineties OSHA PSM compliance directive, and the more recent OSHA Petroleum Refining and Chemical National Emphasis Programs (NEP). Citations specific to PSM are being generated at a fair pace by OSHA in recent months, and the recent settlement between BP Texas City and OSHA has a strong prescriptive element of “timely response” in it.

What’s the practical answer to what “timely” means ?

That is a lengthy discussion with many wrinkles and folds, but it’s a discussion that needs to be had in each plant site and company, the process industries, and with the regulators.

Certainly, in the regulatory field, there are areas where deadlines and milestones are clear-cut – miss the date for a consent agreement or a settlement, and it’s difficult to assert a “timely” response. In PSM and RMP, companies and facilities typically set “deadlines” for completion of actions, especially those arising from Process Safety Incident Investigations (PSII), Process Hazard Analyses (PHA), and Process Safety Compliance Audits (PSCA), deadlines that are developed within a performance based regulatory environment.

There are some subtleties to consider.

Is a facility setting reasonable deadlines in their recommendations from PSII, PHA, and PSCA ? Ambitious goals all been all the rage in management circles for more than a decade (e.g., “You want six months ? Do it in two months !”), and many safety professionals find themselves in a bind between managers who demand rapid action, and a definite shortage of available resources, most especially where such efforts are seen as “non-value added work” by the people who are responsible for the procedure (re)-writing, re-design, new maintenance, or other such duties with tight deadlines.

At the same time, the industry has seen a distinct pushback on meeting deadlines that could result in shutdowns or an accelerated turnaround cycle, with repeated decisions to set deadlines for completion around existing turnaround cycles to maintain production, and avoid “unnecessary shutdowns”. With turnaround cycles being extended to maintain production, this could stretch out completion of actions for five or more years in some cases.

Practically speaking, neither an aggressively ambitious approach or the systematic delay of actions for years is an easily defensible approach for compliance.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the early usages for the term “deadline” date back to the nineteenth century :

1. A line that does not move or run.

2. A line drawn around a military prison, beyond which a prisoner is liable to be shot down.

The latter definition is definitely macabre but perhaps apropos for regulatory compliance, especially when concerned with citations or even criminal prosecution. Deadlines should be well determined and thoughtfully fixed when considering performance based regulatory compliance. Missing deadlines for an appreciable number or fraction of actions would seem to be a recipe for regulatory citations. Such a failing speaks to a direct breakdown of management systems under PSM, and could, in certain cases, lead to OSHA citations classified as Willful.

Setting all material actions as much as five or six years out also has substantial questions associated with the decision. If an issue has appreciable safety implications, why is it acceptable to continue with an identified hazard for so long ? Is the risk of a planned shutdown so much larger than the identified hazard ? If so, doesn’t this call into question the safety of any start-up or shutdown, and imply that these hazards are not adequately controlled ? And what then is the excuse for not extending an unplanned shutdown for a longer period to address closure of the some recommendation action plans, especially where these do not require capital equipment installation but instead “standard” repair and maintenance efforts ?

OSHA has taken definite notice of this issue in the recent OSHA – BP Texas City agreement where Deputy Assistant Secretary Jordan Barab commented,

The agreement requires BP to complete pressure relief and layer of protection analyses of all of the equipment in all of the refinery’s 28 process units according to definite schedules and to take interim measures to protect employees from any risks of catastrophic releases discovered in the pressure relief and layer of protection analyses including, if necessary, shutting the process down.

There may be some ambiguity in the issues of “…any risks of catastrophic releases discovered…” but the closing part of the sentence, “… if necessary, shutting the process down”, is completely clear and unambiguous, setting out OSHA’s expectation of how to address the findings of technical and hazard analyses. Deputy Assistant Secretary Jordan Barab’s public statement sets a new level of action for “timely response”.

Practically speaking, with recommendation action plans requiring specialist skills, equipment with long lead times for delivery, and the need for a carefully planned effort to implement, undertaking some actions plans when a unit trips and shuts down is impractical, and perhaps even adds the net risk of the shutdown. But if these questions are not addressed in advance through a defined management plan, it’s nearly impossible to refute findings from a regulator of “You should have fixed this during the shutdown.” or “You should have shut the process down immediately to address this issue.”

What should a prudent and thoughtful manager do in these cases ?

Like many areas in this field, there are no simple and easy answers that meet both the ethical and economic drives implicit in running a plant safely in the modern process industries.

However, there are some two simple tests to apply to action plans and the “timely response” to these action plans. Applying such tests in a systematic and even manner to action plans can allow for the development of practical management systems for timely response. The answers to the tests may be very complicated, but the tests are straightforward.

“If it seems to be too good to be true, it probably is !”

Action plans with closures all set within weeks or even months are plans that typically assume very large available resources. If a plant site has those resources, well and good, but assigning tasks where a rational person knows the completion date is non-achievable is foolhardy at best, and perhaps “Willful” at worst.

“…I know it when I see it…”

Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart’s comment was made in an entirely different context than PSM/RMP, but the expression has become common to many observances of what should be considered obvious to a reasonable person. If dates for work tasks are placed so far out on a timeline that they are not in sight, there is no honest way to refer to these tasks as “timely”, and most certainly not “as soon as possible”. As a colleague in Odessa, Texas remarks ruefully when people propose obviously unachievable actions to him, “There’s just no way that’s going to pass the red-face test !”

Practically speaking, setting dates for actions that are documentation or procedural in nature should be easy. Even allowing for the development of materials, distribution to all shifts, training of all shifts, this is an exercise in operations management of the shifts. After all, if a plant can train everyone on a new timecard system or a designated human resources issue in several months, how can a simple update to a procedure require three or four years ?

Complete rewriting of major procedures or safe work practices may take longer, but it’s going to be difficult to explain deferring procedures past the next required certification period under PSM (excepting rather obvious cases where the recommendation/action item arises close to the certification date). Still, holding procedural updates up for several years won’t be defensible.

Timetabling equipment related issues is somewhat more complex, but it isn’t like hand solving a third-order partial differential equation. Order times, fabrication times, delivery and installation are staple fare for project managers and project schedulers. Again, this is a management issue that is within the core competency of any properly run company.

Developing a clearly explained risk based priority system is similarly within the range of most competently managed facilities. Most companies will have a defined threshold level for risk where the decision to take operational reductions or shutdowns is elevated within the site or the company to an appropriate managerial level, assuming that the company doesn’t actively discourage elevation of safety issues (a much much larger issue than the one in this discussion, and one with truly immense regulatory and even criminal implications for the managers of such a company).

The trainwreck in this process usually occurs when the risk isn’t extremely high with an imminent hazard, but just below that threshold level, and this decision process is not usually documented as cleanly as one might want to see, especially if an incident occurs, or an outside auditor or regulatory inspector wants to understand the logic of the decision.

At this juncture, one needs to note that there is no OSHA resolution criterion for PHA or PSII recommendations that allows for rejection such as, “It costs too much”, or “We don’t want to take a shutdown now.” One can argue on the need for such criteria – such a discussion between OSHA and the industry should be held at some point, perhaps in rulemaking for updates to PSM – but the fact remains that no compliance directive from OSHA includes these issues.

How does a manager bridge the chasm of competing priorities in an practical effective manner ?

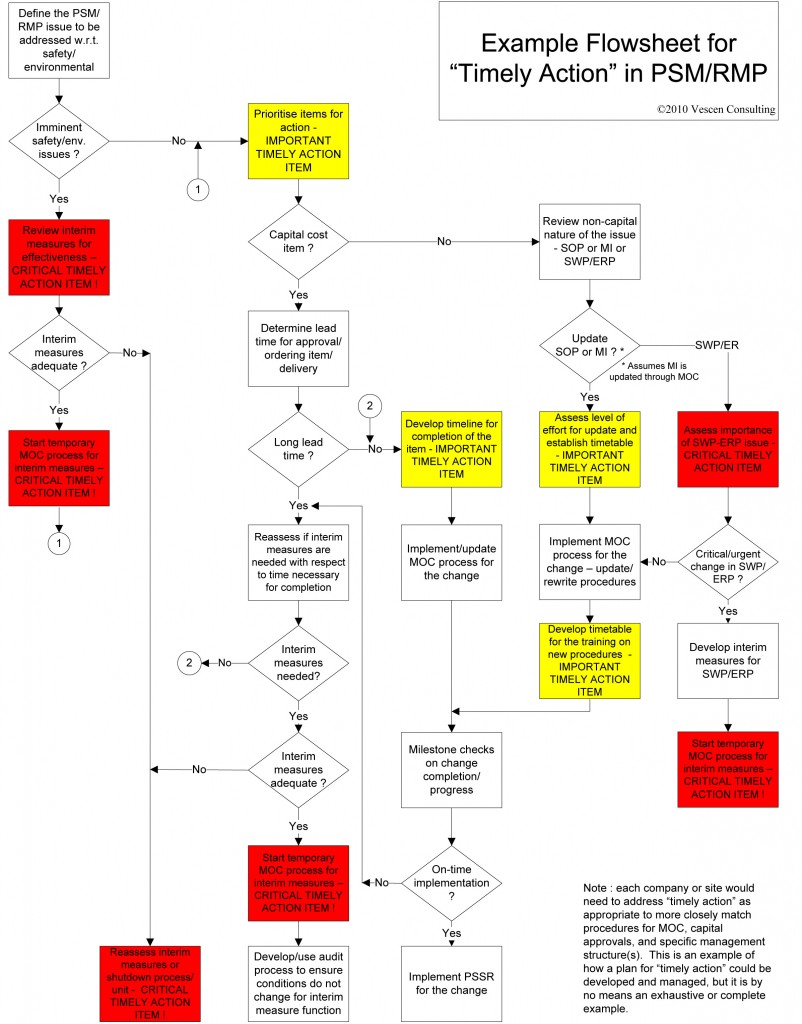

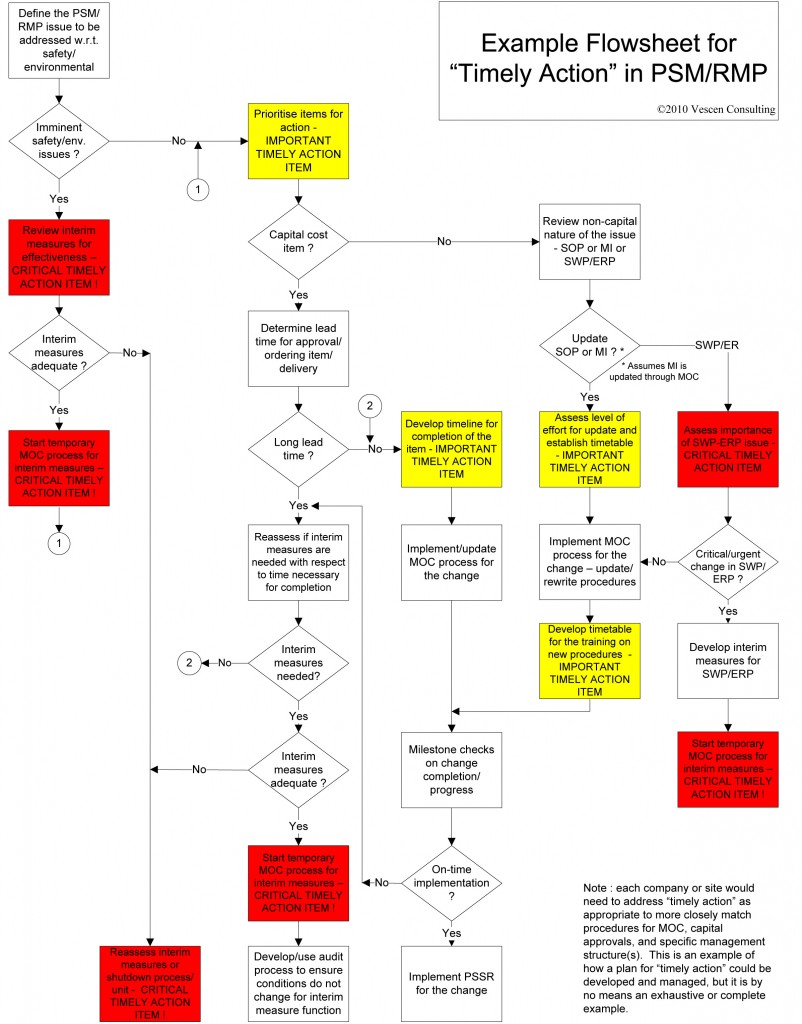

Develop a management plan with specific actions based on the existing management systems for the plant combined with assessments of imminent and non-imminent hazards.

For example, first decide if the issue is an imminent risk. Address obvious areas that fall under capital cost programs or procedural programs. For capital project issues, re-consider the timeline if measures will require an excessive period with a continued hazard in the plant. For procedural issues, establish if the procedures related to emergency response or safe work practices in immediate use in the plant. In all areas establish if interim measures are to be taken, and if these are adequate to the identified hazard. Add in an auditing function to ensure that conditions do not change while interim measures are in place, with a new assessment if this turns out to be the case. Check to make sure that actions are being taken as set out in the timetable.

Most importantly, define what become urgent items for completion, or what could also be called Critical Timely Action Items, getting the highest possible priority for immediate action. One Critical Timely Action Item designation that should be carefully defined is where a process unit should be be shutdown immediately – the need for this to become a management system follows from the comments made by Deputy Assistant Secretary Jordan Barab noted earlier in this post.

One approach for these sorts of management decisions is to develop a flowsheet or decision tree that addresses outcomes from each decision. An example is attached of such a flowsheet – note that this example is not comprehensive, and would not address a specific plant site or company, and as such no warranty or guarantee of regulatory compliance is provided, implied, or even loosely suggested here.

There are other approaches to addressing non-imminent risks in a timely manner, such as identifying the areas that can be completed (relatively) quickly and (relatively) easily, what economists sometimes call “harvesting the low hanging fruit”. That approach can show a clear commitment to due diligence, if implemented carefully.

Straightforward corrections to documentation, removing obsolete or outdated documents from manuals, updating names and responsibilities on call-lists, these are all “low hanging fruit”. Next, develop a list of “targets of opportunity” where an unplanned shutdown would offer the time to complete the actions, such as replacing field pressure gauges, flushing otherwise unavailable systems, or other such items that could reasonably be addressed after a unit has undergone LockOut/TagOut (LOTO) and then appropriate safeing to allow for response to a shutdown. The number of cases where repairs have been completed in an unplanned shutdown but not included action items is large, and exactly on point with this discussion, such behaviour is no longer defensible to regulators.

The key element of meeting the requirements of “timely response” and “as soon as possible” is for a plant site/company to develop and implement well-defined management systems to proactively address issues for completion of PSM/RMP related action plans.

No system will be perfect, quite obviously, but having a practical and functioning management system addresses the question of actions deemed as “…intentional, knowing or voluntary disregard for the law’s requirement, or plain indifference to employee safety and health”…

… That’s what OSHA defines as Willful, something that no manager wants to see in bold print on an official document of citation delivered to the plant by registered mail.